Jokes You Can Use:

Little Johnny was at football practice one day and the coach said

“Who here thinks they can jump higher than the goal posts”

Immediately little Johnny said, “Ooh me sir me”

The coach then said, “But Johnny you are the worst in the team!”

Then Johnny said, “I know, but goalposts can’t jump!”

A school teacher asked her primary six class to construct sentences with the words: defeat, detail, defense.

There was a pause before a pupil raised his hand and said he could make a sentence with them; “The cow jumped over defense and detail went over defeat.”

A distraught older woman is looking at herself in the mirror and crying. Her voice shakes as she says to her husband, “I’m so old. I’m so fat. I look horrible. I really need a compliment.”

Her husband, determined to quickly give his beloved the comfort she needs, exclaims, “Well, you have good eyesight!”

I intend to live forever – so far, so good.

In Australia, a race was proclaimed, with a huge payoff for the winner. The one stipulation was that only ostriches were allowed to run the race. A fellow decided to enter, but not having an ostrich, and hearing that the fastest ostrich in the world was the mascot of the local police department, he stole the bird and entered the race. As luck would have it, when the pistol shot went off to start the race, the ostrich buried its head in the sand and the fellow lost the race.

Moral:

Eileen Award:

- Twitter: Julie Tanner (@julietanner07), Vocab Sushi, That School App,

Advisory:

Radiooooo

Does My Voice Really Sound Like That?

Take it from an expert: It’s weird to hear how your voice really sounds. But why does it sound different to you than everyone else. Hank explains — in a deep, resonant voice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2wThQljxcY&feature=youtu.be

16 Shakespearean Insults

*Warning the *H* word is used.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_Uej8LJ48Q#t=49

Breakfast

Children all over the world eat cornflakes and drink chocolate milk, of course, but in many places they also eat things that would strike the average American palate as strange, or worse.

“The idea that children should have bland, sweet food is a very industrial presumption,” says Krishnendu Ray, a professor of food studies at New York University who grew up in India. “In many parts of the world, breakfast is tepid, sour, fermented and savory.”

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/08/magazine/eaters-all-over.html

Middle School Science Minute

by Dave Bydlowski (k12science or davidbydlowski@mac.com)

I was recently reading the September, 2014 issue of “Science Scope,” a magazine written for middle school science teachers, published by the National Science Teachers Association.

In this issue, I read an article entitled “Moving Ahead With Alternate Conceptions,” written by Aaron Isabelle, Rosemary Millham, and Thais da Cunha. In the article, they explain how alternate conceptions are also referred to as misconceptions, which are deeply ingrained, scientifically inappropriate ideas about something in the physical or natural world. In the article, they state 11 alternate conceptions correlated with the NGSS. An example of an alternate conception is that dinosaurs and cavemen lived at the same time.

From the Twitterverse:

Strategies:

Homework

- A brand-new study on the academic effects of homework offers not only some intriguing results but also a lesson on how to read a study — and a reminder of the importance of doing just that: reading studies (carefully) rather than relying on summaries by journalists or even by the researchers themselves.

- First, no research has ever found a benefit to assigning homework (of any kind or in any amount) in elementary school. In fact, there isn’t even a positive correlation between, on the one hand, having younger children do some homework (vs. none), or more (vs. less), and, on the other hand, any measure of achievement. If we’re making 12-year-olds, much less five-year-olds, do homework, it’s either because we’re misinformed about what the evidence says or because we think kids ought to have to do homework despite what the evidence says.

- Second, even at the high school level, the research supporting homework hasn’t been particularly persuasive.

- It’s easy to miss one interesting result in this study that appears in a one-sentence aside. When kids in these two similar datasets were asked how much time they spent on math homework each day, those in the NELS study said 37 minutes, whereas those in the ELS study said 60 minutes.

- it was statistically significant but “very modest”: Even assuming the existence of a causal relationship, which is by no means clear, one or two hours’ worth of homework every day buys you two or three points on a test.

- There was no relationship whatsoever between time spent on homework and course grade, and “no substantive difference in grades between students who complete homework and those who do not.”

- The better the research, the less likely one is to find any benefits from homework.

- you’ll find that there’s not much to prop up the belief that students must be made to work a second shift after they get home from school. The assumption that teachers are just assigning homework badly, that we’d start to see meaningful results if only it were improved, is harder and harder to justify with each study that’s published.

- many people will respond to these results by repeating platitudes about the importance of practice[8], or by complaining that anyone who doesn’t think kids need homework is coddling them and failing to prepare them for the “real world” (read: the pointless tasks they’ll be forced to do after they leave school).

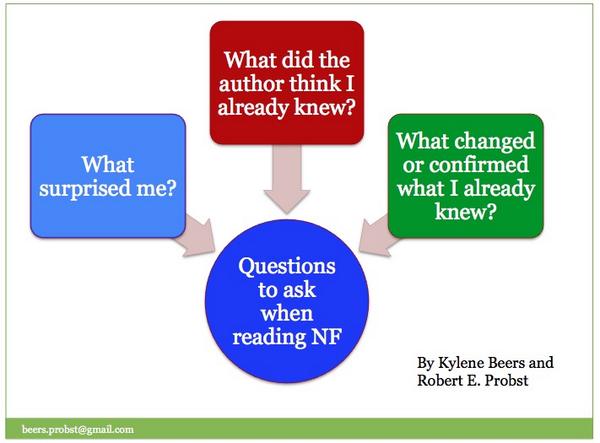

Three critical questions students should keep in mind–any subject, any grade–when reading NF:

https://twitter.com/KyleneBeers/status/515988759171829760/photo/1

Resources:

How Teacher’s Learn

http://thelearningcounsel.com/repository/teachers-as-tech-learners.jpeg

http://thelearningcounsel.com/archives/How-Teachers-Learn

National Cyber Safety Month

National Security Awareness Month

https://plus.google.com/photos/+google/albums/5940699556055522273

ScratchJR

Coding is the new literacy! With ScratchJr, young children (ages 5-7) can program their own interactive stories and games. In the process, they learn to solve problems, design projects, and express themselves creatively on the computer.

Download for the iPad.

http://www.scratchjr.org/index.html

Web Spotlight:

Mute the Messenger

When Dr. Walter Stroup showed that Texas’ standardized testing regime is flawed, the testing company struck back.by Jason Stanford Published on Wednesday, September 3, 2014, at 8:00 CST

- “Rigor” was the new watchword in education policy.

- Testing advocates believed that more rigorous curricula and tests would boost student achievement—the “rising tide lifts all boats” theory. But that’s not how it worked out.

- Texas Education Commissioner Robert Scott, long an advocate of using tests to hold schools accountable, broke from orthodoxy when he called the STAAR test a “perversion of its original intent.”

- To his credit, Committee Chair Rob Eissler began the hearing by posing a question that someone should have asked a generation ago: What exactly are we getting from these tests?

- Stroup sat down at the witness table and offered the scientific basis behind the widely held suspicion that what the tests measured was not what students have learned but how well students take tests.

- his testimony to the committee broke through the usual assumption that equated standardized testing with high standards. He reframed the debate over accountability by questioning whether the tests were the right tool for the job. The question wasn’t whether to test or not to test, but whether the tests measured what we thought they did.

- Stroup argued that the tests were working exactly as designed

- Stroup had caught the government using a bathroom scale to measure a student’s height.

- The scale wasn’t broken or badly made. The scale was working exactly as designed. It was just the wrong tool for the job. The tests, Stroup said, simply couldn’t measure how much students learned in school.

- Rep. Jimmie Don Aycock (R-Killeen) brought Stroup’s testimony to a close with a joke that made it perfectly clear. “I’d like to have you and someone from Pearson have a little debate,” Aycock said. “Would you be willing to come back?”

- “Sure,” Stroup said. “I’ll come back and mud wrestle.”

- Stroup had picked a fight with a special interest in front of politicians. The winner wouldn’t be determined by reason and science but by politics and power.

- Pearson’s real counterattack took place largely out of public view, where the company attempted to discredit Stroup’s research. Instead of a public debate, Pearson used its money and influence to engage in the time-honored academic tradition of trashing its rival’s work and career behind his back.

- standardized tests have become the pre-eminent yardstick of classroom learning in America, and Pearson is selling the most yardsticks.

- Stroup started asking after he thought he found a way to use cloud computing to expose poor, minority children to basic math concepts using calculus.

- The same kids branded as failures by the state tests embraced the project, using the cloud technology collaboratively to learn basic math concepts. This was the breakthrough that everybody—Kress, Perot and lawmakers in Austin—had been looking for.

- However, the students’ scores rose only 10 percent, a statistically valid variance but hardly the change that he had observed in the classroom.

- Using UT’s computing power, Stroup investigated. He entered the state test scores for every child in Texas, and out came the same minor variances he had gotten in Dallas. What he noticed was that most students’ test scores remained the same no matter what grade the students were in, or what subject was being tested. According to Stroup’s initial calculations, that constancy accounted for about 72 percent of everyone’s test score. Regardless of a teacher’s experience or training, class size, or any other classroom-based factor Stroup could identify, student test scores changed within a relatively narrow window of about 10 to 15 percent.

- Stroup knew from his experience teaching impoverished students in inner-city Boston, Mexico City and North Texas that students could improve their mastery of a subject by more than 15 percent in a school year, but the tests couldn’t measure that change. Stroup came to believe that the biggest portion of the test scores that hardly changed—that 72 percent—simply measured test-taking ability. For almost $100 million a year, Texas taxpayers were sold these tests as a gauge of whether schools are doing a good job. Lawmakers were using the wrong tool.

- The paradox of Texas’ grand experiment with standardized testing is that the tests are working exactly as designed from a psychometric (the term for the science of testing) perspective, but their results don’t show what policymakers think they show.

- Stroup concluded that the tests were 72 percent “insensitive to instruction,” a graduate- school way of saying that the tests don’t measure what students learn in the classroom.

- After correcting what Pearson interpreted as the mislabeled column, Way wrote, the tests were “only 50 percent” insensitive to instruction.

- This alone was a startling admission. Even if you accepted Pearson’s argument that Stroup had erred, here was the company selling Texas millions of dollars’ worth of tests admitting that its product couldn’t measure half of what happens in a classroom.

- A student in the third grade did as well on a math test as that same student did in the eighth grade on a language arts test as the same student did in the 10th grade on a different test. Regardless of changes in school, subject and teacher, a student could count on a test result remaining 50 to 72 percent unchanged no matter what. Stroup hypothesized that the tests were so insensitive to instruction that a test could switch out a science question for a math question without having any effect on how that student would score.

- “teachers account for about 1% to 14% of the variability in test scores,” largely confirming Stroup’s apparently controversial conclusion.

- If it’s true that the test measured primarily students’ ability to take a test, then, Stroup reasoned to the House Public Education Committee in June 2012, “it is rational game theory strategy to target the 72 percent.” That means more Pearson worksheets and fewer field trips, more multiple-choice literary analysis and fewer book reports, and weeks devoted to practice tests and less classroom time devoted to learning new things. In other words, logic explained exactly what was going on in Texas’ public schools.

- we end up with adults and professionals spending most of their time gaming the system.”

- Rep. Eissler never called another hearing to have the debate between Stroup and a Pearson representative as Rep. Aycock had suggested. Eissler retired from the Legislature and now lobbies for Pearson.

- Tax law allows corporations to establish charitable foundations. What tax law doesn’t allow is endowing a nonprofit to supplement the parent corporation’s profit-driven mission. Last December, Pearson paid a $7.7 million fine in New York state to settle charges that the Pearson Foundation “had helped develop products for its corporate parent, including course materials and software,” reported The New York Times.

http://www.texasobserver.org/walter-stroup-standardized-testing-pearson/

Random Thoughts . . .

Book

deliberate [sic] Optimism: reclaiming the JOY in education by Dr. Debbie Silver, Jack C Berckemeyer, and Judith Baenen.

“Recharge the optimism that made you an educator in the first place! School is where students and staff should feel safe, engaged, and productive – and choosing optimism is the first step toward restoring healthy interactions necessary for enacting real change.”